The following is an interview I conducted with my good friend, Tyler Fry. Tyler is a bartender at Chicago’s famed “The Violet Hour.” The bar was the recipient of the James Beard Foundation’s 2015 award for Outstanding Bar Program. In this article, Tyler shares with us his knowledge surrounding tea cocktails.

Is there any history to using tea in cocktails?

Absolutely! There certainly is old, historical precedent for tea in booze and mixed drinks, dating as far back as 1727. While we don’t necessarily see tea in old cocktails or being used in the mixological sense that we think of today, tea was an ingredient used in very early punches, which really predate even the most “classic” of cocktails. Punches were large format social cruxes which eventually gave way to cocktails, sours and the advent of all those single-serving drinks that we now revere in our contemporary cocktail culture.

“Only now that tea is being treated better in the global food/beverage scene, especially in the West, just as cocktails are being given their proper due are we seeing the two crafts come together and seeing tea leaves be employed thoughtfully within the context of the cocktail.”

Punches were comprised of booze (strong), water (weak), sweet, sour, and spice. Fast-forward to the earliest of cocktails (what we now call the “Old Fashioned” cocktail) and the foundation is booze, sugar, water, bitters (which is essentially your spice.)

The grandaddy of American bar celebrities, Jerry Thomas pointed out that you can use tea in place of water (wait, isn’t that basically what tea is?) in your punches for added complexity. Who’da thunk! Most of this probably would have been green tea in the US at the time. The sharp, bitter, astringent edge of tea and herbal complexity basically pre-dates the use of bitters which were the defining agent in the “cocktail” and fills the same niche in terms of drying, rounding and complexi-ma-fying a cocktail.

That being said, the historical precedent ends there. Cocktails as we know them today are of the post-punch variety (slings, bittered slings, sours, fizzes, duos and trios, etc.) Punch is only finally being ushered back into the mix, albeit completely altered from its historic identity.

Throughout the dark ages of the cocktail, tea has certainly been incorporated into booze as a mixer, diluter, or added to punches (for punch, read “frat juice.”) But this doesn’t overlap in any way with the resurgence of tea culture in the culinary scene; the push toward orthodox, whole leaf tea brewed properly. Only now that tea is being treated better in the global food/beverage scene, especially in the West, just as cocktails are being given their proper due (this “mixology” sh*t never went away or died out Tom Cruise style in Japan, just sayin’…) are we seeing the two crafts come together and seeing tea leaves be employed thoughtfully within the context of the cocktail.

For a bit of perspective, let’s look at what Gaz Reagan, one of the champions at the frontline of the cocktail revival, had to say in his seminal work, “The Joy of Mixology,” on “Various and Sundry Supplemental Ingredients” – tea:

Tea is seldom used as a cocktail ingredient, but when it’s called for there is simply no substitute… I have experimented a little with this ingredient, and advise you to make a somehwhat stronger brew than you would if you were going to drink it from a cup.

These are the cocktail books on which many contemporary bartenders and I cut our teeth, and you can see right here that the basis for using tea leaves in a cocktail was always to brew a liquid infusion and add that liquid to a mixed drink of booze and other modifiers. That’s perfectly fine if you want to dilute the flavor of tea, dilute the flavor of a spirit and end up with a drink that is ultimately less than the sum of its parts. I can think of one context in which that would be lovely, and it’s a winter-time hot toddy. Masala chai is your best friend here. But outside of that narrow context, we prefer to aim for gestalt. Bartenders aim to highlight their primary spirit in a cocktail and use all other ingredients to elevate one another to new heights. Pouring a slug of strong tea onto a dram of booze is not going to elevate a cocktail, only drown it. Bitters (which we use by the drop and by the dash) are essentially concentrated, intense, little dashes of herbal tea magic! So why can’t the leaves, like other herbs and spices, see their full potential in the cocktail scene? Here’s how they can.

How did you get started with tea cocktails?

I would not be in the spirits and cocktail business if it were not for my background in the tea industry. I was always curious about the art of the bar, but long before I ever got my start, I was working in tea. I am an infusion geek at heart, and spent many years studying, tasting, reading about, traveling around, working in, and obsessing about tea – the art of drying and altering green leaves into a cuppable herb in order to then reconstitute that herb with water and imbibe thereof. Who would have thought that you can reconstitute that same herb with a different liquid? Perhaps booze?

When I was working for a tea company in 2007 (this is before I was 21) we hosted one of our many tea tasting events, but with the twist of serving alcoholic tea drinks. We invited a local liquor rep, who later became a mentor and set me on my path in the bar industry, to serve tea cocktails. The vast majority of the drinks (I didn’t taste them at the time, of course; that would be illegal) were of the style described above. “Brew strong tea. Add to booze. Drink a sh*tty cocktail.” Except for one, and it’s probably the most important tea cocktail in modern mixology: The Earl Grey, courtesy of Audrey Saunders of the Pegu Club, NY.

It sounds simple and obvious, but until Audrey’s genius, the idea of taking tea leaves and steeping them in a spirit such as gin to get a boozy tea infusion, and building your cocktail as per usual off of that spirit was revolutionary. You get all the flavor of the the tea, sacrifice no flavor of the spirit (and here I reiterate: as bartenders, we focus on highlighting the base spirit of a drink) and you aren’t diluting or muddying flavors, textures, and proof by dumping a brew of tea (no matter how strong, let’s face it, it ain’t gonna work out) into a balanced medley of cocktail ingredients.

Okay, so how do you achieve the sanctity of the tea cocktail?

What Audrey did was take a straightforward, classic gin sour (a silver sour, with egg white, to be exact) with the use of Earl Grey-infused gin and created, not only a modern classic, but to me personally, one of the most influential modern classics. The Earl Grey sour bridged my love of tea with spirits. It was the first drink I experimented with when I realized, “Oh yeah, I should juice fresh lemon instead of using that crap in the yellow bottle;” and, “Oh yeah, using powdered egg whites instead of just cracking an egg open doesn’t really do the trick.” Give me a break. I was 19!

I wouldn’t have made my way into cocktails without it. I wouldn’t have met Audrey’s pupil and bar maestro, Toby Maloney (my boss) without it. And I wouldn’t be working to push tea forward in the spirits industry, making new cocktails that employ tea thoughtfully to its full potential, if it weren’t for this simple, simple, groundbreaking cocktail.

The Procedure: Steep 4 Tbsp of loose Earl Grey tea into a 750ml bottle of gin for two hours. Strain.

There is plenty of room to jiggle these measurements depending on the proof of the spirit.

“ABV basically works similarly to water temperature in terms of infusing tea: the higher the proof, the quicker bolder extraction of flavors you will get.”

ABV (Alcohol by Volume) basically works similarly to water temperature in terms of infusing tea: the higher the proof, the quicker bolder extraction of flavors you will get. You can’t really isolate which flavors you want, like you can with tea by cold-brewing for less astringency and more sweetness. In alcohol, it’s pretty much all or nothing (even the non-water solubles like bright, green chlorophyll, which wouldn’t normally steep out in tea,) but you can use this to your advantage. You can use less tea for less flavor, or steep for a shorter time. You can make smaller batches and only use a Tbsp or two, or you can make large batches. Be warned, though, the tea measurements don’t extrapolate directly to a large scale. The larger the batch you want to infuse, the lower the ratio of tea needs to be. 4 Tbsp might be perfect for a 750ml bottle of gin, but 12 Tbsp might be plenty for 4 bottles. There will also be loss of liquid through absorption, so use proportionally less and steep longer.

Are there specific spirits that hold tea better than others?

There is no reason why any particular spirit should hold tea better or worse than another. The question lies more in how that spirit and its infusion play in the balance of the cocktail as a whole, which unfortunately demands a little more mixology background and cocktail basics to understand. Basically, know the difference between your shaken (citrusy, refreshing, effervescent drinks) and stirred (silky, dense, booze-driven cocktails with almost all alcoholic ingredients.) Again, tea is astringent, and in that sense can work almost like bitters, but you’ll have far better luck with tea in the base spirit of a sour, with plenty of acid and sugar to round out and cut the tannic edge of the tea. Try the same thing in a stirred drink like a Manhattan and you’re in for a rough time. Remember, proof in the spirit works like water temperature. You’ll get more intense flavor steeping into a base spirit than you will a lower-proof wine, vermouth, or liqueur.

Plenty of people come to me with the brilliant idea of making a chai-spiced Manhattan or a Smoky Lapsang Souchong Old Fashioned, but when you steep black tea in the base spirit for a stirred cocktail, you’re suddenly faced with intense astringency, awful texture and a drink that you won’t want to finish, no matter how good it might taste. If you want to make a stirred, spirit-forward drink like a Manhattan, you’re better off steeping the tea into the sweet vermouth. The lower proof will give you a lighter, slower extraction of flavors, the vermouth has enough sugar to round out and take the edge off the tea, AND you’ll be using less of the vermouth than the base spirit, so it won’t overpower the cocktail. Trust me, you’ll still get plenty of chai spice or Lapsang Souchong smoke.

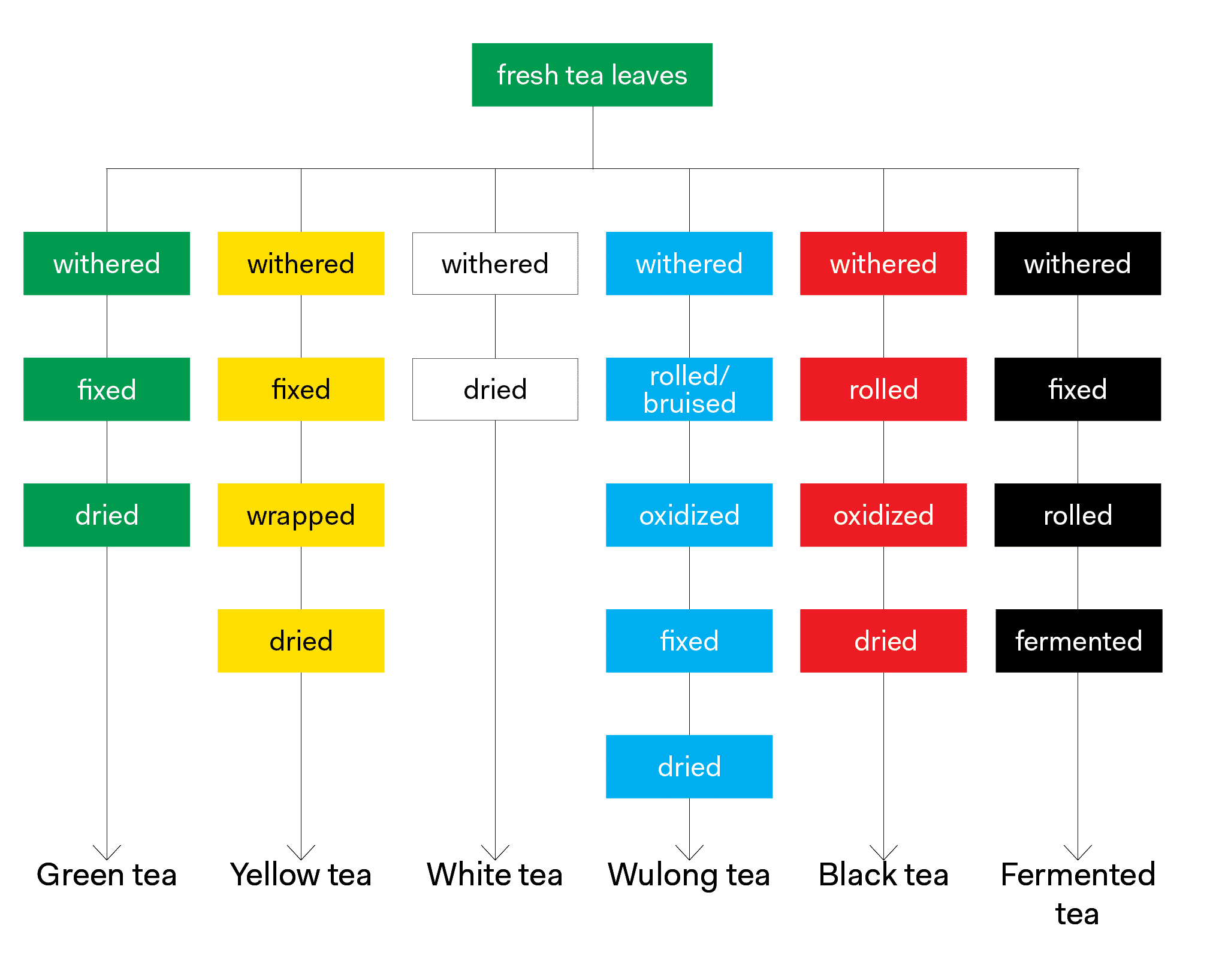

Pairing spirits with tea is a matter of finding flavor complements. Masala chai and rum are a no-brainer. You can’t buy a better spiced rum off the shelf. I promise. Gin goes with most things for it’s floral, herbaceous, botanical qualities. Whiskey and other dark spirits probably prefer the more oxidized, roasted teas. I don’t know who hit on chamomile and Scotch first, but I see a lot of people doing it; they both just go so well with floral, honied, nutty ingredients.

It’s important to know your teas, how they infuse in water, different temperatures, before you worry about steeping them in spirits. Herbal teas are less finicky than true tea leaf. Caffeine free herbs aren’t going to go bitter on you in the way tea can. White tea, pu’er tea, roasted teas are a little more forgiving than black tea and green tea. You have to consider the mass vs. volume ratios of each tea. White tea and chamomile are big and fluffy, but chamomile isn’t going to go bitter on you. You only have to consider how intensely you want the flavor to be infused into the spirit. Oolongs can be tightly rolled and dense. You should get used to using gram measurements, but that’s really only necessary in large batches. For home use, 4 Tbsp of tea per 750ml bottle of booze is good. My baseline infusion time is 2 hrs. Less if it’s highly tannic or steeping in the base spirit of a minimal stirred drink; more if it’s herbal, caffeine free, big, fluffy tea or if it’s being steeped into a lower proof modifier (vermouth) or going into a very busy, shaken cocktail with lots of juice, syrups, modifiers, etc.

Below are two tea-infused cocktails: the seminal “Earl Grey” by Audrey Saunders, and one of my own which demonstrates how to tackle a trickier infusion of black tea into a spirit-driven Manhattan-style cocktail, the “Hori Smoku.”

The Earl Grey (Adapted from Audrey Saunders)

By Tyler Fry

- 2.0 oz Earl Grey-infused Beefeater Gin

- .75 oz Lemon Juice

- .75 oz Simple Syrup

- 1 Egg White

- Shake all ingredients without ice to emulsify.

- Shake with ice.

- Strain, up, into a cocktail glass.

- Garnish with the oils of a lemon peel, expressed over the cocktail.

- Discard the peel.

Hori Smoku

By Tyler Fry

- 1.0 oz Sailor Jerry Spiced Rum

- 1.0 oz Yamazaki 12yr Japanese Whisky

- 1.0 oz Lapsang Souchong-infused Carpano Antica Sweet Vermouth

- +.25 oz Zucca Rabarbaro

- Stir all ingredients with ice.

- Strain over a large chunk of ice in a rocks glass.

- Garnish with a lemon peel, expressed over the cocktail and inserted into the glass.