Venture With Me Down the Rabbit Hole

I went down the rabbit hole as they say researching a single topic for my book, Tea: A User’s Guide. This time the rabbit hole was related to South Korean tea: balhyocha and hwangcha to be exact. Some tea merchants selling the same product will call it hwangcha and some will call it balhyocha. There seems to be no single definition of either of these tea terms and even more disconcerting, neither fits cleanly into standard tea classifications. What follows are excerpts from Matt of the wonderful Mattcha tea blog and discussions I’ve had with two South Korean tea experts followed by my own take on the subject.

From Mattcha (post one / post two):

“Hadong Green Tea Institute launched a research project [in 2009] looking into the different forms of production in the hopes of finding a standard formula at which they can mass produce. They claimed that because Balhyocha production has much to do with instinct, there really is no standard way of production.”

The processing of Balhyocha typically follows these steps: Withering -> Rolling -> Heaping -> Drying

“Koreans generally consider Balhyocha to be in the yellow tea category (Hwangcha) because they call the production step of vigorous shaping/rolling, and then slow drying [“men huang”] or “yellowing phase”. Also, the final product pours yellow. So as a very matter a fact sensory judgement- the tea is a yellow tea.”

Mina Park (from an email discussion / Mina works for Hankook Tea):

“Hwangcha is not a yellow tea. You may find that description on the web here and there because when initially released it in the US, the Korean words “hwang” and “cha” literally translates to “yellow/golden” and “tea”. Hwangcha is a partially oxidized tea. In Korea, it is categorized as a “bu-bun-balhyocha” (“bu-bun” meaning “partial/partially”). The method of oxidation, which is different from an oolong or from other oxidized tea, is what sets this apart from other oxidized teas.”

Gabriel Furnari (from an email discussion / Gabriel runs Jiri Mountain Tea):

“When the terms balhyocha and hwangcha are used by the locals here and elsewhere some confusion understandably arises. Balhyo translates into ‘fermented.’ The leaves of hwangcha have oxidized and falls under ban-balhyo (which means half, semi, or partially oxidized). This may not be entirely accurate in terms of Korean hwangcha. The information I have on Korean hwangcha is based on what I saw from a Korean tea processing chart which was written in Korean, and gleaned from an experienced tea artisan who has traveled to China and learned tea processing techniques from a Chinese tea master.”

“However, it truly is tricky because from what I have seen, and have been told by more than one tea artisan here in Hwagae Valley is that hwangcha is more the exception than the rule. Most of the balhyocha made and sold in Korea and outside of it is made with tea leaves that have been more oxidized than Korean hwangcha. Having said that, the majority of Korean fermented/oxidized tea made is called balhyocha even if it is hwangcha.”

“Balhyo is the general term for any tea or food (kimchi comes to mind), for that matter, that has undergone any sort of fermentation in Korea. As you might already know the Korean yellow tea and Chinese yellow tea are similar in name only, hwangcha. That is where the similarities end.”

“Hwangcha (yellow) is a type of balhyocha (partially oxidized tea), but not quite a fully oxidized black tea. Every tea artisan uses a slightly different processing technique and temperature guidelines to make their own unique Hwangcha. I once asked a Korean tea artisan here in Hwagae Valley while sipping green tea with him to define Balhyocha. Without hesitation he said it was black tea, not yellow tea. I don’t really know the true reason for the way he responded tha way that he did. It may have been easier to say black tea without explaining what yellow tea is or maybe he didn’t want to confuse this foreigner.”

“I learned that the Korean tea makers adopted yellow tea from the Chinese tea processing classification, but tweaked it to complement their own processing methods and to make a unique brand of Korean fermented yellow tea. It does not have a long traditional use when compared to Korean nokcha from what I understand. That is why there is no clear understanding of it outside of Korea. I don’t think its yellow tea or black tea according to ‘standard’ tea processing charts.”

Discussion

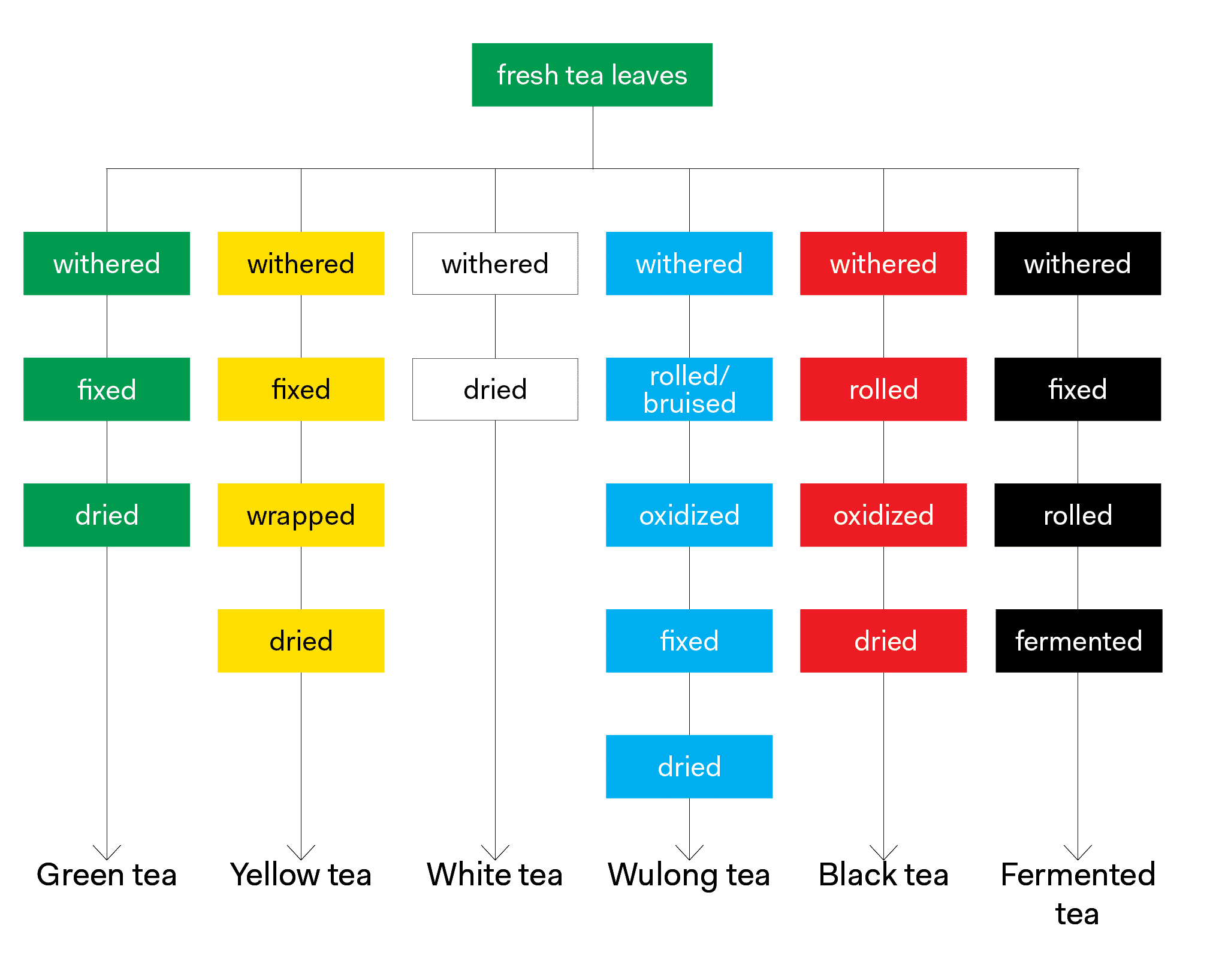

From these discussions/excerpts, it is easy to discern that balhyocha (발효차) translates to “fermented tea” which really refers to “oxidized tea.” This means that any oxidized tea is balhyocha, including hwangcha (황차). You may have noticed that Mina and Gabriel added a bit of detail here with their usage of the terms bu-bun bal-hyo-cha (부분 발효차) and ban-balhyocha (반 발효차) which are similar terms that mean partially oxidized and half-oxidized respectively. So the big question that remains is…. what type of tea is hwangcha? Let’s compare what we know of the hwangcha process to my tea processing chart:

Is hwangcha a yellow tea?

Hwangcha is similar to yellow tea in that it has a heaping process and the resulting infusion is yellow. But hwangcha does not go through a kill-green process like traditional yellow tea. This is the only major difference. The drying process technically functions as a kill-green here, but this is done last.

Is hwangcha a wulong tea?

Hwangcha is similar to oolong in that it is semi-oxidized. But that’s it. hwangcha isn’t bruised repeatedly like an oolong, and Hwangcha doesn’t go through a kill-green process like oolong. Also, oolong does not have a heaping process.

Is hwangcha a black tea?

Hwangcha is similar to black tea if we call the heaping phase oxidation. Because there is no kill-green when it comes to hwangcha, it is safe to say that oxidation is occuring during heaping. Black tea is withered, rolled, oxidized, and dried. The only problem here is that hwangcha is not typically as oxidized as a black tea, but because of the similarities between the processes, hwangcha can be considered a “lightly oxidized” black tea. Brother Anthony of Taize in his book The Korean Way of Tea compares hwangcha to black tea on page 37: “Korean tea makers have begun producing small quantities of oxidized tea, usually known as hwangcha that is similar in taste to the black/red tea familiar to the rest of the world.”