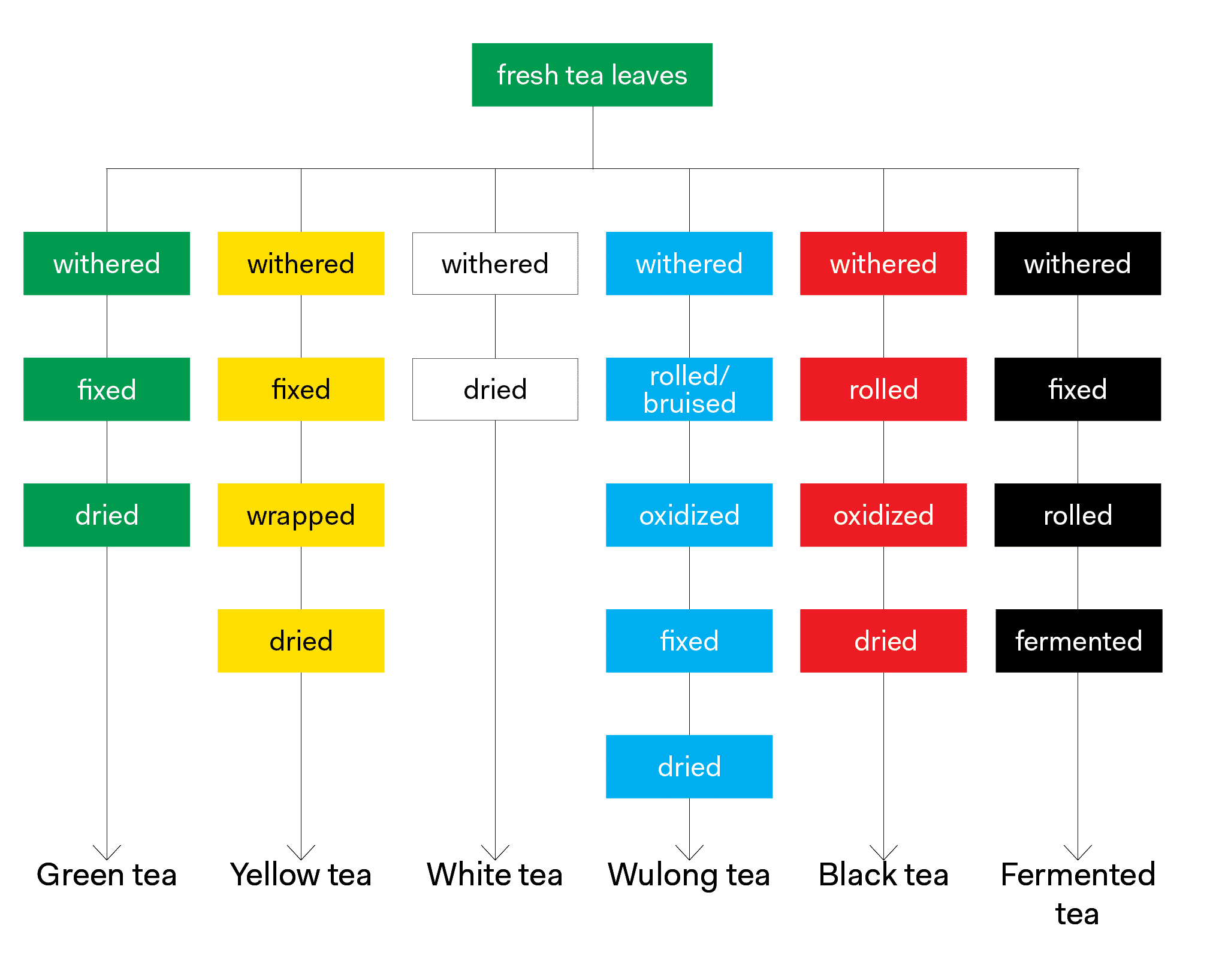

When shopping for tea you’re bound to come across some pretty bogus sounding marketing claims—tea picked by monkeys, affordable tea from 3000 year old trees, tea that will make you lose weight—so you’d be wise to be skeptical about Oriental Beauty, a so-called “bug-bitten” wulong tea originating in Taiwan. You may have heard that its flavor is owed to damage by a particular insect which starts the oxidation process, and therefore it is always from tea fields that are never sprayed with pesticides. In order to clear up some of the misunderstandings about this tea, we first need a quick primer on the science of plant defense chemistry.

Plants are smarter than they look. When a plant is attacked, it might appear to be completely unaware, but, in reality, it is mounting defenses, sometimes even before an attack begins. When an insect bites into a plant leaf, the plant can sense not only that its leaves are being damaged, but it can sense who is doing the damage. That’s important, because defenses that work against, say, a caterpillar, might not work well against an aphid or a beetle. Plants defend themselves in myriad ways. They can make their leaves less nutritious, they can create toxins or release stored ones, or they can use airborne chemicals to call for help from the enemies of their enemies, to name a few options.

These changes in leaf chemistry are exactly what is going on with Oriental Beauty. It all starts with a bite from a tiny green insect, only about 3mm long at full size, called the tea green leafhopper (Empoasca onukii)*. These tiny insect bites don’t leave visible holes on the leaves, but they do damage the plant. This means you can’t really tell if an Oriental Beauty tea is “real” based on the appearance of a brewed leaf. These bites are often described as “beginning the oxidation process.” While it’s true that any time plant leaves are damaged some oxidation happens, I wouldn’t say these tiny bites begin any tea processing steps—that is, bug-bitten tea leaves are still essentially unoxidized and you could process them as a green tea if you wanted to. Despite the small size of their wounds, leafhoppers still present a threat to the tea plant which responds by releasing airborne volatile chemicals. Although it isn’t clear what exactly these chemicals do in this specific example (there is some evidence they attract small spiders that eat the leafhoppers), this particular blend of chemicals is different from the blend produced when other insects attack. It just so happens that these leafhopper-specific chemicals smell nice if you’re a human, and make for a very tasty cup of tea. You can actually smell the aroma of Oriental Beauty in the field—before the leaves are even plucked—because it’s something that the living plants produce to defend themselves. So it is true that the unique flavors of real Oriental Beauty tea (and other bug-bitten teas) are largely due to bug-bites, but it’s not the bugs themselves you’re tasting or their saliva, rather the chemicals that the tea plant releases in response to those bugs.

Typical symptoms of leafhopper damage–brown stippling and yellowish leaf color.

Of course there are other variables that go into making a good quality Oriental Beauty besides insect attack. For example, the cultivar matters. According to many experts, the best Oriental Beauty is made from a cultivar called qing xin da mao. Teas produced using this cultivar have an incredible cooling sensation on the palate, and when layered on top of the sweet aroma and smooth taste produced by the response to leafhoppers, it produces an incredibly balanced and complex (and expensive) cup of tea. Most inexpensive Oriental Beauty tea on the market, however, is probably not made with this cultivar, as other cultivars like tieguanyin are more common, and valued by farmers because they are suitable for producing a wide range of tea types.

Even though leafhoppers are necessary to make Oriental Beauty tea, farmers still have reason to control their population. According to Mr. Liu, the manager at Shanfu Tea Company in Shaxian, Fujian Province, China, you can’t make good quality Oriental Beauty if there is too little or too much damage by leafhoppers. He explained that a little damage by leafhoppers reduces the bitterness of tea, but too much damage actually increases the bitterness. His claims of a “Goldilocks” effect have not been investigated scientifically (that’s part of what I’m doing for my PhD), but my point is that to make high-quality Oriental Beauty, it’s not as simple as just forgoing all pest control.

Mr. Liu uses several methods to keep leafhopper damage in check. The simplest of them is simply to pluck the leaves when they have the right amount of damage. Leafhopper damage can change the chemistry of a tea leaf in as quickly as 2 days, so farmers monitor their fields very closely and pluck leaves when the damage level and amount of leaf growth are appropriate. Plucking the leaves knocks down the leafhopper population because it takes away their food source and removes eggs, which are laid in the young buds. Mature leaves are too thick for their tiny piercing mouthparts, so they move on to greener pastures or die. Mr. Liu also manages the leafhoppers by controlling weeds. He has noticed that if there are tall grasses between rows of tea plants that there are more leafhoppers on the tea plants. He believes that the grasses provide more cover for the leafhoppers from the mid-day heat and from predators like spiders and their population grows. By removing those grasses, Mr. Liu can knock down the population to fine-tune the amount of damage a tea field gets. Scientifically speaking, this idea is totally plausible, but hasn’t been tested, so take it with a grain of salt.

Left to Right: Dr. Han from the Tea Research Institute, Mr. Zeng the general manager of Shanfu Tea Company, Eric Scott, Dr. Orians from Tufts University, and Mr. Liu, the manager at Shanfu Tea Company.

Even though tea farmers have many tools at their disposal to control insects besides synthetic chemical sprays, the claim that Oriental Beauty tea is always pesticide free just doesn’t hold water. Pesticides include any chemicals farmers use to kill pests such as diseases, insects, or weeds. Pesticides can be synthetic or natural like, say, capsaicin (the active ingredient in chili oil), pyrethrin (extracted from chrysanthemum), or viruses that attack certain pests. So a farmer can use pesticides for weeds, or for a fungal disease, or release a virus that kills only caterpillars, and none of those things are going to affect the leafhoppers. In fact, at Mr. Liu’s farm they sprayed for weeds a week before harvesting one of their non-organic fields to produce Oriental Beauty. So you may hear a tea shop tell you that their Oriental Beauty is pesticide free, even if it isn’t certified organic, because it must be produced that way. Well, that isn’t necessarily true. And remember, even if it is certified organic, that only limits the list of pesticides that can be used—it doesn’t mean pesticide-free. Regardless if the tea is organic or not, if tea farmers do their jobs well, then any pesticide residues in tea should be at safe levels. Even if you buy some Oriental Beauty that really is totally pesticide free, it doesn’t mean those tea fields never get sprayed. Oriental Beauty is only produced in the summer when leafhopper populations are high enough. Those same fields are being plucked and processed as other styles of tea in the spring and farmers might need to spray to control pests since insect damage isn’t desirable for, say, a green tea.

So next time you hear some dubious claims about insects and tea, remember: bug-bitten teas do actually develop their particular aroma and flavor in response to attack by a specific insect, the tea green leafhopper; bug-bitten teas are NOT necessarily pesticide-free, even if they are labeled “organic”; plants are super smart and amazing; and everything in the World of Tea is more complicated than it looks at first glance.

*Sometimes you’ll see different scientific names for the tea green leafhopper—Jacobiasca formosana in Taiwan, Empoasca onukii in Japan, and Empoasca vitis in China—but recent research shows that they are probably all the same species, Empoasca onukii.