Have you ever wondered why Japanese green teas are so green? And why Chinese green teas are not as bright green, but are typically yellower? The reason lies in the processing steps for each tea and in particular the “kill-green” step of the processing some tea types. The term kill-green is derived from the Mandarin shaqing (杀青), which means “killing the green.”

Kill-green is also referred to as “de-enzyming” or “fixing” and is a process of tea manufacture used to halt the oxidative browning of tea leaves by denaturing the enzymes responsible for oxidation– polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase. Think of an apple, once it is sliced open, it quickly turns brown; however, the apples in apple pie are not brown because the heat used to bake the pie denatured the polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in the apples and prevented enzymatic browning (same goes for potatoes, avocados, bananas, etc,).

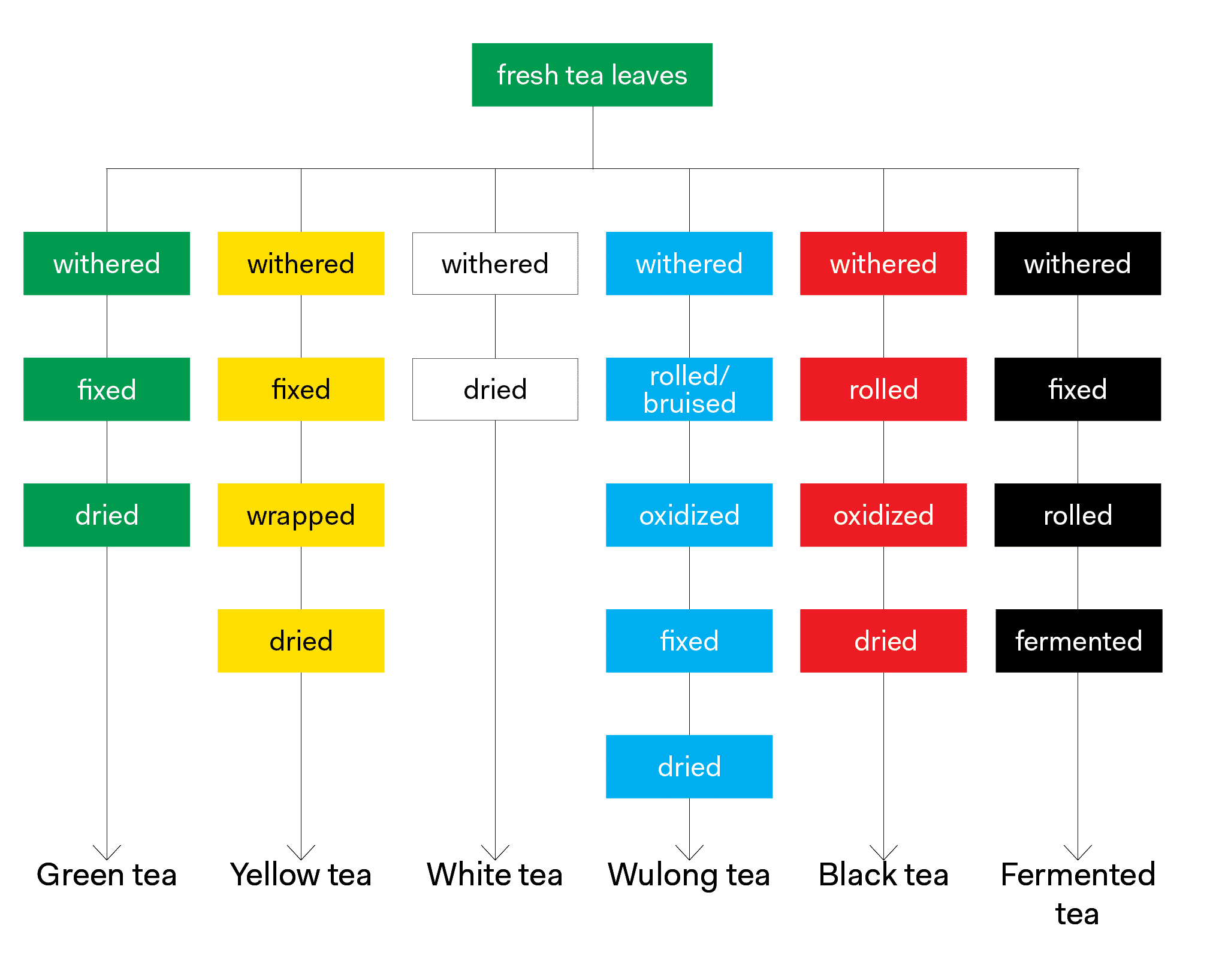

In tea, the leaves must be heated to approximately 150 degrees Fahrenheit to halt oxidation. The longer it takes to heat the leaves to the temperature necessary for denaturing polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase, the more aromatics will develop. For example, green teas that are steamed reach this temperature more quickly than teas that are pan fired and as a result remain bright green and vegetal and lack a diverse aroma. Pan fired teas invoke what’s called the maillard reaction which is a form of non-enzymatic browning that produces toasty notes in a tea and finished tea leaves that are usually yellower in appearance. In general, most Chinese green teas are pan-fired (photo above), and most Japanese green teas are steamed (photo below). There are other methods for “killing the green” — sometimes a heated tumbler is used or an oven-like machine, while some teas are sun-dried and in this case, oxidation is halted not by heat, but by dehydration. The kill-green process of tea manufacture is commonly employed in the production of green, yellow, oolong, black tea when dried, and post-fermented teas.

This post is part of a larger post dealing with the initiation, control, and cessation of oxidation. It’s also part of a series of posts covering other individual processing steps: withering, oxidation and drying. And finally, my tea processing chart.